Cooking surface: 2/5 Poor (fragile, low melting point)

Conductive layer: N/A (tin is never the main heat conductive layer)

External surface: N/A Poor (tin is too soft for exterior use)

Example: Mauviel

Health safety: 4/5 Good (tin is mostly but not totally non-reactive)

—–

DESCRIPTION AND COMPOSITION

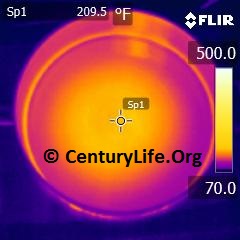

Tin is an extremely soft metal that you can scratch with your fingernail.1 Tin transitions from shiny “beta” tetragonal tin to rhombic tin between 161C and 202.8C (321.8F and 397.04F).2 It’s still tin, just in a different crystal arrangement and slightly less shiny. Tin melts at 231.9C (449.42F).3

Tin is used in copper cookware as a lining because tin resists corrosion, is nontoxic, and is relatively non-reactive compared to bare copper. Ingesting large amounts of copper can lead to negative health consequences, so always have your tin-lined copper re-lined once you see large bare areas of copper peeking through.4

IS TIN TOXIC?

Tin is not toxic in small amounts, especially elemental tin, hence the proverbial “tin can” for food.5 Unless you plan to gnaw on your tin-lined cookware, it should not be a problem to absorb a milligram here or there from tin.

TIN-LINED COPPER VS STAINLESS-LINED COPPER

Frankly I would avoid both since copper cookware tends to sell for small fortunes, and you can get thick aluminum for much cheaper and at a lower weight and still get very good thermal conductivity.

But if you must have copper than stainless-lined is the way to go for most people. Here’s why: