Cooking surface: 4/5 Very Good (comparable to stainless steel in stickiness)

Conductive layer: 5/5 Excellent (highest thermal conductivity among all metals)

External surface: 3/5 Good (silver is only about a hard as aluminum, so it scratches easily on stovetop grates)

Examples: Soy Turkiye (Soy Türkiye)

Health safety: 5/5 Excellent (ingesting trace amounts of silver is completely safe, and silver is naturally antimicrobial)

—–

DESCRIPTION AND COMPOSITION

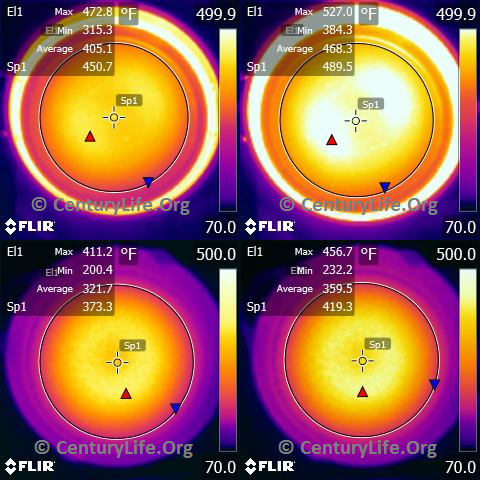

Silver is the most thermally conductive metal in the universe that we know of. It even beats copper by about 10%, depending on metal purity. (In order of highest to lowest thermal conductivity: silver (406 W/m*K), copper (385), gold (314), aluminum (205), typical cookware-grade aluminum alloy (~160), platinum (72), tin (67), cast iron/carbon steel (~50), stainless steel (16), enamel/ceramic/glass (~1), water (0.6), and PTFE such as Teflon (0.25). [Read more…]